Integrating over all orbitals: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (26 intermediate revisions by 5 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

Computing expectation values of observables ''O'' over all Kohn-Sham orbitals is an important concept relevant to most ''ab initio'' calculations. | |||

Typically, we can evaluate these expectation values as integral over all orbitals | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

\langle O \rangle = \sum_n \frac{1}{\Omega_{\mathrm{BZ}}} \int_{\Omega_{\mathrm{BZ}}} | |||

O_{n\bold{k}} \, \Theta(\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}} - \epsilon_{n\bold{k}}) \, d^{3}k, | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

where < | where Ω<sub>BZ</sub> is the volume of the Brillouin zone, | ||

''O''<sub>n'''k'''</sub> is the expectation value of the observable with a single Kohn-Sham orbital, | |||

a | and Θ is the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heaviside_step_function Heaviside step function] and limits the integral to orbitals with eigenvalues ϵ<sub>n'''k'''</sub> below the Fermi energy ϵ<sub>F</sub>. | ||

When evaluating the integral above numerically, we need to address two concerns: | |||

(i) We need to discretize the '''k'''-point integral since we do not know the analytic expression of the observable. | |||

(ii) A sharp function cutoff like the Heaviside function is numerically unstable so we need robust smearing methods. | |||

== Integrating over '''k''' points == | |||

Discretizing the '''k'''-point integral involves replacing the continuous integral over the Brillouin zone by a '''k'''-point mesh.{{cite|baldereschi:prb:1973}}{{cite|chadi:prb:1973}}{{cite|monkhorst:prb:1976}} | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

| Line 22: | Line 23: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

A '''k'''-point mesh consists of '''k'''-point coordinates and associated weights ''w''<sub>'''k'''</sub>. | |||

In general, any mesh could be chosen but for periodic boundaries the optimal one are equidistant grids. | |||

In VASP, we select this sampling by a {{FILE|KPOINTS}} file or the {{TAG|KSPACING}} tag. | |||

We can improve the integrals further because the crystal exhibits certain symmetries. | |||

Often we can deduce the value ''O''<sub>n'''k'''</sub> from a different symmetry-equivalent '''k''' point. | |||

VASP automatically analyzes the symmetry of the crystal and reduces the '''k''' point mesh to the irreducible Brillouin zone. | |||

The weights of each irreducible '''k''' point measure how many equivalent '''k''' points exist in the reducible Brillouin zone. | |||

== Integrating near the Fermi energy == | |||

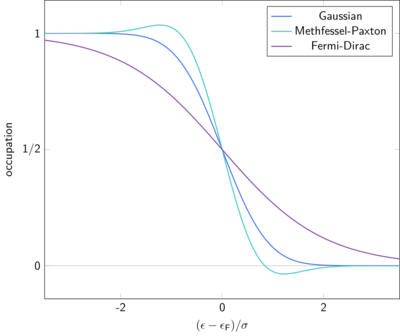

[[File:integrated.png|thumbnail|400px|Occupation of different smearing techniques near the Fermi energy ϵ<sub>F</sub>. | |||

The energy is measured in units of the smearing σ ({{TAG|SIGMA}}). | |||

The Methfessel-Paxton method (cyan) is closer to the step function than the Gaussian distribution (blue) but also has nonmonotonous features. | |||

The smearing Fermi-Dirac distribution (purple) corresponds to a temperature but is much broader at the same value of σ.]] | |||

We want to replace the Heaviside step function by a smooth equivalent to make the integral numerically stable. | |||

Otherwise small changes in the energies would toggle the inclusion of a sample ''O''<sub>n'''k'''</sub> close to the Fermi energy. | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

\sum_{\bold{k}} | \sum_{n\bold{k}} \Theta(\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}} - \epsilon_{n\bold{k}}) \ldots \to \sum_{n\bold{k}} f_\sigma(\epsilon_{n\bold{k}}) \ldots | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Here, the occupations ''f''<sub>σ</sub>(ϵ<sub>n'''k'''</sub>) approach 1 for energies far below the Fermi energy ϵ<sub>F</sub> and 0 for energies far above it. | |||

The parameter σ determines how wide the broadened step function is. | |||

In the figure, we illustrate the different smearing methods implemented in VASP. | |||

The Fermi-Dirac smearing ({{TAGO|ISMEAR|-1}}) uses σ as the temperature in the Fermi-Dirac distribution{{cite|mermin:pra:1965}} | |||

= | <math> | ||

f_\sigma(\epsilon) = \Bigl[\exp(\frac{\epsilon-\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}}}{\sigma})+1\Bigr]^{-1}~. | |||

</math> | |||

One can also use the complementary error function ({{TAGO|ISMEAR|0}}) which results from integrating a Gaussian distribution as the occupation function.{{cite|devita:phd:1992}} | |||

This leads to a narrower edge than the Fermi-Dirac distribution for the same σ and a faster approach to the asymptotic behavior | |||

a | |||

<math> | |||

f_\sigma(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{2} \text{erfc}\Bigl[\frac{\epsilon-\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}}}{\sigma}\Bigr]~. | |||

</math> | |||

Methfessel and Paxton {{cite|methfessel:prb:1989}} developed higher order approximations to the step function ({{TAGO|ISMEAR|0|op=>}}). | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

f_\sigma(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{2} \text{erfc}\Bigl[\frac{\epsilon-\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}}}{\sigma}\Bigr] + \exp\Bigl[-\bigl(\frac{\epsilon-\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}}}{\sigma}\bigr)^2\Bigr] \sum_{i=1}^{n} \frac{(-1)^i}{4^i i! \sqrt\pi} H_{2i-1}\Bigl[\frac{\epsilon-\epsilon_{\mathrm{F}}}{\sigma}\Bigr]~. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

or | Here, ''n'' is the order of the expansion and ''H''<sub>j</sub> is the j-th Hermite polynomial. | ||

The first order Methfessel-Paxton smearing is shown in the figure. | |||

This method leads to an even narrower distribution but introduces a nonmonotonous behavior that can lead to problems in semiconductors and insulators. | |||

A consequence of these broadening techniques is that the total energy is no longer variational (or minimal). | |||

It is necessary to replace the total energy by some generalized free energy | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

F = E - \sum_{n\bold{k}} w_{\bold{k}} \sigma S[f_\sigma(\epsilon_{n\bold{k}})]. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

For the Fermi-Dirac statistics, we might interpret this as the free energy of the electrons at some finite temperature σ = ''k''<sub>B</sub>''T''. | |||

There is no straightforward interpretation of the free energy in the case of Gaussian or Methfessel-Paxton smearing. | |||

Despite this, it is possible to obtain an accurate extrapolation for σ → 0 from results at finite σ using the formula | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

E_0 = E(\sigma \to 0) = \frac{1}{2} (F + E)~. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

( | ''E''<sub>0</sub> is a meaningful physical quantity for the ground state energy of the system. | ||

Importantly, the [[:Category:Forces|calculated forces]] are the derivatives of the free energy ''F'' and not of ''E''<sub>0</sub>. | |||

the | Nonetheless, the difference of the forces is generally small and acceptable it a suitable σ is used. | ||

of the | |||

When we consider ''E''<sub>0</sub> as our target property, the smearing methods serve as a mathematical tool to obtain faster convergence with respect to the number of k-points. | |||

Generally, the Gaussian broadening requires more careful tuning of the width σ compared to the Methfessel-Paxton method. | |||

If σ is too large, the energy ''E''(σ → 0) will converge to the wrong value even for an infinite '''k'''-point mesh. | |||

If σ is too small, we require a much denser '''k'''-point mesh and a significantly larger computational cost. | |||

With the Methfessel-Paxton method the sharper edge usually averts the necessity of tuning σ. | |||

However, since the occupation function is nonmonotonous, it is '''not''' suitable to describe systems with a bandgap. | |||

== Tetrahedron method == | |||

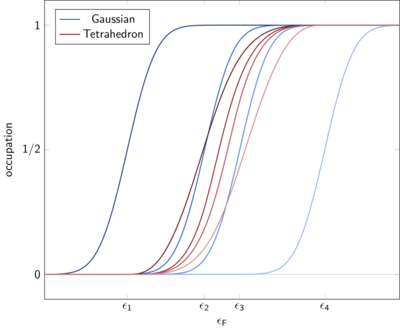

[[File:tetrahedron.png|thumbnail|400px|Four '''k''' points forming a single tetrahedron with ordered eigenvalues ϵ<sub>1</sub>, ϵ<sub>2</sub>, ϵ<sub>3</sub>, and ϵ<sub>4</sub>. | |||

The lines show the occupation of the orbitals with changing Fermi energy ϵ<sub>F</sub> where the darkest line corresponds to the lowest and the brightest line to the highest eigenvalue. | |||

For the Gaussian smearing (blue) every '''k''' point is considered individually leading to half filling when the Fermi energy reaches the eigenvalue. | |||

The tetrahedron method (red) does not fill any orbital if the Fermi energy is outside of the bounds of the tetrahedron. | |||

]] | |||

The tetrahedron method is an alternative approach to address the sharp edge of the Heaviside step function. | |||

Instead of considering each '''k''' point individually, we triangulate the '''k'''-point mesh, i.e., we split it into as many tetrahedra as necessary to cover the whole Brillouin zone. | |||

We use a linear interpolation of the band energies ϵ<sub>n'''k'''</sub> within each tetrahedron the band energies. | |||

Blöchl{{cite|bloechl:prb:1994}} derived correction terms to cancel the linearization errors of the tetrahedron method. | |||

With this interpolation, we can solve integral over the Brillouin zone analytically considering each tetrahedron individually. | |||

It does not require a choice of a width σ like the broadening methods. | |||

The figure illustrates the difference between broadening and interpolation method. | |||

A broadening method like the Gaussian smearing considers every '''k''' point individually. | |||

Therefore, it will start filling the orbital as soon as the Fermi energy reaches the width σ of the broadening. | |||

In the tetrahedron method, the '''k''' points of the tetrahedron only get occupied once the Fermi energy exceeds the lowest eigenvalue. | |||

Similarly, it is completely filled once the Fermi energy exceeds the maximum value. | |||

As a consequence, the occupations of the different '''k''' points are much closer to each other. | |||

Overall, the tetrahedron method yields very accurate occupations with minimal user input. | |||

It is very well suited to obtain accurate integral (e.g. total energy) and band onsets (e.g. density of state). | |||

The main drawback is that the Blöchel's correction of the linearization errors is not variational with respect to the partial occupancies. | |||

Therefore the calculated forces might be wrong by a few percent. | |||

If accurate forces are required we recommend a finite temperature method. | |||

== Determining the Fermi energy == | |||

One important example of integrals over all orbitals is the calculation of the Fermi energy. | |||

In this case, the observable is identity and the sum of all occupations should be equal to the number of electrons ''N''<sub>e</sub> | |||

<math> | <math> | ||

\sum_{n\bold{k}} f_\sigma(\epsilon_{n\bold{k}}) = N_{\mathrm{e}}~. | |||

</math> | </math> | ||

This leads to a straightforward interval-bisection algorithm to compute the Fermi energy. | |||

We guess bounds for the Fermi energy and then compute the sum of all occupations in the middle of the interval. | |||

If this results in a number larger than the number of electrons, we replace the upper bound otherwise we replace the lower one. | |||

Note that this algorithm is not deterministic for systems with a bandgap, where any Fermi energy in the gap would be fine. | |||

VASP achieves more consistent results for these system by a good initial guess for the Fermi energy (see {{TAG|EFERMI}}). | |||

This potentially leads to an early exit of the bisection algorithm so that only for metals many iterations of bisection are considered. | |||

== Related tags and sections == | |||

| | {{FILE|KPOINTS}}, | ||

| | {{TAG|ISMEAR}}, | ||

| | {{TAG|SIGMA}}, | ||

[[Smearing technique]] | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

<references/> | <references/> | ||

---- | ---- | ||

[[Category:Electronic | [[Category:Electronic minimization]][[Category:Electronic_occupancy]] | ||

[[Category:Crystal momentum]][[Category:Theory]] | |||

Latest revision as of 13:00, 28 February 2025

Computing expectation values of observables O over all Kohn-Sham orbitals is an important concept relevant to most ab initio calculations. Typically, we can evaluate these expectation values as integral over all orbitals

where ΩBZ is the volume of the Brillouin zone, Onk is the expectation value of the observable with a single Kohn-Sham orbital, and Θ is the Heaviside step function and limits the integral to orbitals with eigenvalues ϵnk below the Fermi energy ϵF.

When evaluating the integral above numerically, we need to address two concerns: (i) We need to discretize the k-point integral since we do not know the analytic expression of the observable. (ii) A sharp function cutoff like the Heaviside function is numerically unstable so we need robust smearing methods.

Integrating over k points

Discretizing the k-point integral involves replacing the continuous integral over the Brillouin zone by a k-point mesh.[1][2][3]

A k-point mesh consists of k-point coordinates and associated weights wk. In general, any mesh could be chosen but for periodic boundaries the optimal one are equidistant grids. In VASP, we select this sampling by a KPOINTS file or the KSPACING tag.

We can improve the integrals further because the crystal exhibits certain symmetries. Often we can deduce the value Onk from a different symmetry-equivalent k point. VASP automatically analyzes the symmetry of the crystal and reduces the k point mesh to the irreducible Brillouin zone. The weights of each irreducible k point measure how many equivalent k points exist in the reducible Brillouin zone.

Integrating near the Fermi energy

We want to replace the Heaviside step function by a smooth equivalent to make the integral numerically stable. Otherwise small changes in the energies would toggle the inclusion of a sample Onk close to the Fermi energy.

Here, the occupations fσ(ϵnk) approach 1 for energies far below the Fermi energy ϵF and 0 for energies far above it. The parameter σ determines how wide the broadened step function is.

In the figure, we illustrate the different smearing methods implemented in VASP.

The Fermi-Dirac smearing (ISMEAR = -1) uses σ as the temperature in the Fermi-Dirac distribution[4]

One can also use the complementary error function (ISMEAR = 0) which results from integrating a Gaussian distribution as the occupation function.[5]

This leads to a narrower edge than the Fermi-Dirac distribution for the same σ and a faster approach to the asymptotic behavior

Methfessel and Paxton [6] developed higher order approximations to the step function (ISMEAR > 0).

Here, n is the order of the expansion and Hj is the j-th Hermite polynomial. The first order Methfessel-Paxton smearing is shown in the figure. This method leads to an even narrower distribution but introduces a nonmonotonous behavior that can lead to problems in semiconductors and insulators.

A consequence of these broadening techniques is that the total energy is no longer variational (or minimal). It is necessary to replace the total energy by some generalized free energy

For the Fermi-Dirac statistics, we might interpret this as the free energy of the electrons at some finite temperature σ = kBT. There is no straightforward interpretation of the free energy in the case of Gaussian or Methfessel-Paxton smearing. Despite this, it is possible to obtain an accurate extrapolation for σ → 0 from results at finite σ using the formula

E0 is a meaningful physical quantity for the ground state energy of the system. Importantly, the calculated forces are the derivatives of the free energy F and not of E0. Nonetheless, the difference of the forces is generally small and acceptable it a suitable σ is used.

When we consider E0 as our target property, the smearing methods serve as a mathematical tool to obtain faster convergence with respect to the number of k-points. Generally, the Gaussian broadening requires more careful tuning of the width σ compared to the Methfessel-Paxton method. If σ is too large, the energy E(σ → 0) will converge to the wrong value even for an infinite k-point mesh. If σ is too small, we require a much denser k-point mesh and a significantly larger computational cost. With the Methfessel-Paxton method the sharper edge usually averts the necessity of tuning σ. However, since the occupation function is nonmonotonous, it is not suitable to describe systems with a bandgap.

Tetrahedron method

The tetrahedron method is an alternative approach to address the sharp edge of the Heaviside step function. Instead of considering each k point individually, we triangulate the k-point mesh, i.e., we split it into as many tetrahedra as necessary to cover the whole Brillouin zone. We use a linear interpolation of the band energies ϵnk within each tetrahedron the band energies. Blöchl[7] derived correction terms to cancel the linearization errors of the tetrahedron method.

With this interpolation, we can solve integral over the Brillouin zone analytically considering each tetrahedron individually. It does not require a choice of a width σ like the broadening methods. The figure illustrates the difference between broadening and interpolation method. A broadening method like the Gaussian smearing considers every k point individually. Therefore, it will start filling the orbital as soon as the Fermi energy reaches the width σ of the broadening. In the tetrahedron method, the k points of the tetrahedron only get occupied once the Fermi energy exceeds the lowest eigenvalue. Similarly, it is completely filled once the Fermi energy exceeds the maximum value. As a consequence, the occupations of the different k points are much closer to each other.

Overall, the tetrahedron method yields very accurate occupations with minimal user input. It is very well suited to obtain accurate integral (e.g. total energy) and band onsets (e.g. density of state). The main drawback is that the Blöchel's correction of the linearization errors is not variational with respect to the partial occupancies. Therefore the calculated forces might be wrong by a few percent. If accurate forces are required we recommend a finite temperature method.

Determining the Fermi energy

One important example of integrals over all orbitals is the calculation of the Fermi energy. In this case, the observable is identity and the sum of all occupations should be equal to the number of electrons Ne

This leads to a straightforward interval-bisection algorithm to compute the Fermi energy. We guess bounds for the Fermi energy and then compute the sum of all occupations in the middle of the interval. If this results in a number larger than the number of electrons, we replace the upper bound otherwise we replace the lower one.

Note that this algorithm is not deterministic for systems with a bandgap, where any Fermi energy in the gap would be fine. VASP achieves more consistent results for these system by a good initial guess for the Fermi energy (see EFERMI). This potentially leads to an early exit of the bisection algorithm so that only for metals many iterations of bisection are considered.

Related tags and sections

KPOINTS, ISMEAR, SIGMA, Smearing technique

References

- ↑ A. Baldereschi, Phys. Rev. B 7, 5212 (1973).

- ↑ D.J. Chadi and M.L. Cohen, Phys. Rev. B 8, 5747 (1973).

- ↑ H.J. Monkhorst and J.D. Pack, Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188 (1976).

- ↑ N.D. Mermin, Phys. Rev. 137, A1441 (1965).

- ↑ [ A. De Vita, PhD Thesis, Keele University 1992; A. De Vita and M.J. Gillan, preprint (Aug. 1992).]

- ↑ M. Methfessel and A.T. Paxton, Phys. Rev. B 40, 3616 (1989).

- ↑ P.E. Blöchl, O. Jepsen, and O.K. Andersen, Phys. Rev. B 49, 16223 (1994).